Sometime near the start of April I needed to research some top-down combat implementations on the GameBoy. This initial quest sparked a tangential curiosity, which would consume most of my month. I started by playing the Japanese release only Kaeru no Tame ni Kane wa Naru, or “For Frog The Bell Tolls“ for the GameBoy. I then followed that up with The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening for the GameBoy and GameBoy Color. After that I dipped my toes in The Legend of Zelda: Oracle of Ages, also for the GameBoy Color. All three games seem to share the same game engine, and their stark differences inspired me to find out more about how they came about, and who made them.

✧༺♥༻✧

It’s frankly laughable that I started my research into GameBoy-era combat systems with For Frog The Bell Tolls. While the game could be described as a classic RPG where a pair of princes adventure across distant lands to rescue a princess damsel, the most notable feature of the game is that it is an RPG with no battles at all.

Well, there are battles, but they are deterministic in outcome. When the player touches an enemy, the two collapse into a cartoon fisticuff dust cloud. As the two combatants exchange unseen blows, their health depletes. The player loses a heart, then the monster loses a heart, then the player loses a heart, etc, until one person dies. There is no input, no action, no dice rolls. As soon as the battle begins, the victor is certain.

To progress through the game, the player has to acquire equipment that improves their fighting ability. For example, the player can find additional health, or they can get a weapon that deals more damage. This is typical RPG fare, but by removing the chance and skill from battles, they have turned the battles into the same “lock and key” sequences that have always existed outside of RPG battle systems. At one point there was an evil tree blocking my way, and I realized that the developers knew definitively that I could not pass through until I had located an additional heart and collected enough money to buy a saw weapon. Every single encounter is transparently part of a grand fetch quest. And I loved it.

Without skill or chance, there is no pressure in any fight. I cannot be good nor bad at the game. Although antithetical to the laws of “good game design,” this was shockingly relaxing to play. All ambiguity and pretense was discarded. Battles lose all drama, sure, but they also pass by in the snap of a second. Fetch quests are often derided because of their tedium, but For Frog The Bell Tolls revealed to me that it is the slow battles that cause that tedium.

As someone who likes to approach studying games by looking at “fun friction,” this approach startled me, and I had to know how it came about. In an interview translated on Shmuplations, programmer Yasuhiko Fuji recounts that the battle system was completely remade three times. He was still in college while working on the game, and was not confident in his design abilities. Ultimately, he decided that the best approach would be to simplify the combat system. What we can learn from this is that the shipped combat system was not what was originally planned. In fact, to my eyes the combat seems “simplified” to the point of being a cut feature. I find this genuinely impressive. Combat systems are the core feature for most RPGs, and most games do not ship with their core feature cut! For Frog The Bell Tolls is a wonderful game, and playing it was unlike anything I have played before. I came to this game looking for combat mechanics, and I left with the lesson that hey, maybe you don’t need them.

✧༺♥༻✧

Except that in my case, I did actually need them. So I moved onto the next game, Link’s Awakening, which I had always heard was the follow-up to For Frog The Bells Toll by the same team. This, it turns out, is not true. If the credits are to be believed, then only the composer worked on both titles. What is true is that both games appear to share the same game engine. The software appears to have the same collision systems and movement, and both utilize a technique for shifting from top-down rooms to side-scrolling rooms. And who were the people utilizing and building on top of the technology from For Frog The Bell Tolls? At the helm was Takashi Tezuka, who wanted to bring his previous title, “A Link To The Past” to handheld.

I would argue that Link’s Awakening is an improvement from what came before. Perhaps because of the smaller platform and less executive oversight, the narrative has greater personality compared to previous Zeldas. Random weirdness in the narrative coexists harmoniously with deeply considered and elegantly constrained design. The smaller screen forces an economy of level design that leads to the densest gameplay per pixel in a Zelda game. Without the technology for scrolling, each screen has to have something interesting to do in it. For Frog The Bell Tolls also had a quirky story, but its serviceable map layout reveals, by contrast, the skill of the Zelda team’s planners. This game benefits from the team’s experience of making A Link To The Past, but gets to utilize ideas too weird for such a high profile title. Further, its development was likely made possible by constructing atop an existing game engine rather than starting from scratch.

The people who made that engine weren’t around for Link’s Awakening. Where were they, then? Fuji, the programmer whose interview I referenced earlier, went on to work on Super Metroid instead. In fact, most of the staff did — Yoshio Sakamoto went from scenario writer to director, graphic designer Masahiko Mashimo continued making background art, both character designer Tomoyoshi Yamane and director Toru Osawa shifted to object design. (Don’t worry about Osawa’s downgrade, though, he then directed Ocarina of Time). There are certainly more parallels to be seen between For Frog The Bell Tolls and Link’s Awakening than there is with Super Metroid, but videogames are mysterious like that.

✧༺♥༻✧

I had so much fun playing Link’s Awakening that I immediately fired up the next handheld Zelda game: Oracle of Ages. This game is one of a pair made by Capcom, the other being Oracle of Seasons. Both of them use Link’s Awakening as a base — not just building off the game engine, but also repurposing many art graphics. Played back to back, these visual similarities really emphasize the differences in level design, and unfortunately the first impression is not favorable.

The Oracle games utilize enhanced scrolling technology that allows for rooms to be larger than a single screen. While this opens up many possibilities for level design, the feature is not used with much restraint. Rooms are large, open, and empty. While Link’s Awakening has every square tile carefully considered, Oracle of Ages baffled me with blocks and level features scattered around at random. In early dungeons I wasted an hour pushing on objects, searching for secrets, because I could discern no other reason for those objects to be there. The inconsistent utility and larger spaces made it more exhausting to travel from one space to the next. Unlike the previous two games, I did not pick it back up after I put it down.

Despite my play experience, I am still fascinated by the result of a new staff. Capcom making an entry in Nintendo’s flagship series was a big deal! While inexperienced with designing the game elements — especially compared to the veterans on Link’s Awakening — giving Capcom’s staff the chance to build this experience would yield incredible future returns. The director, Hidemaro Fujibayashi, would lead Capcom’s The Minish Cap, which is a Zelda game I like quite a bit. He would also go on to direct Breath of the Wild, a game you may have heard of, and that Nintendo seems pretty pleased with. The other planners on the Oracle games would go on to be the lead designers on Devil May Cry 5 and The Last Guardian. That’s pretty incredible!

✧༺♥༻✧

So what are we supposed to do with all this information? I have strayed very far from my quest to learn more about top-down GameBoy combat systems. But I found something much more interesting. I found deeply divergent design approaches that begged for explanation. All of them were born from circumstance, but specifically the circumstance of the people who made them. For Frog The Bell Tolls was made by young new developers with great technical savvy. Link’s Awakening used that base as a platform for veterans to toy around with their after hours ideas. Oracle of Ages/Seasons was loaned that platform to bring in more new voices, one of whom would become instrumental to Nintendo’s 2017 turnaround. I’ve got a new theory that Takashi Tezuka’s games prioritize density, while Hidemaro Fujibayashi encourages vastness. More than anything, though, I am hungry to learn more about the history of individual contributions on every game I play, to better understand what makes them all so different.

✧༺♥༻✧

Along this same subject, I came across a documentary called Star Wars Within a Minute. It had been mentioned within a podcast, and thankfully is easily accessible on YouTube and Disney+. This documentary takes a 48 second scene from Revenge of the Sith and goes through every single department that had a hand in it. This means producers, concept artists, previs artists, costume designers, caterers, post production staff, accountants, everything. They interview representatives from each department, but the complete credits are shown as they go through each. The documentary is ostensibly a fluff piece meant to demonstrate how impressive the scale of the film is, but it still manages to humanize the vast amount of work on all films. I do not know the caterer’s life story, but I now know better the kinds of handprints left on any blockbuster.

✧༺♥༻✧

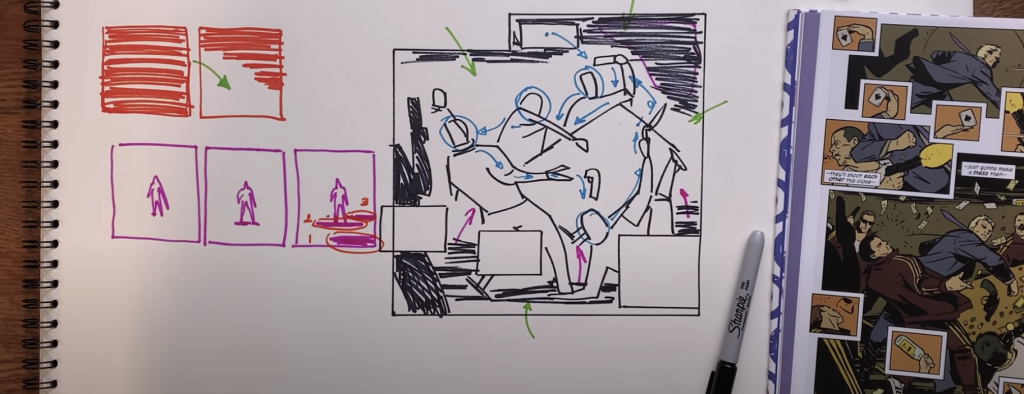

Films are made by hundreds of people, but even more intimate mediums like comic books can benefit from this kind of documentary work. My absolute favorite new YouTube series has been Elsa Charretier’s comic art case studies. In them, she breaks down the visual language within a single page or panel, and uses her professional expertise to explain step by step how the studied artist arrived at their conclusions. She often redraws panels in order to show how different decisions lead to different effects. Her case studies are valuable lessons in negative space and pacing, but they also serve to highlight what makes these master artists unique. By replicating the thought process of these artists, she demystifies the technical aspects of image making while also showing how there can be several approaches to each problem. Plainly seeing the list of information that must be communicated coupled with the creative solutions makes the contributions of the artist obvious.

For people outside of comic book circles it may seem strange to need to declare that the artists are important contributors. Unfortunately, the western comics industry can often treat artists as interchangeable assets. Coverage tends to prioritize writers, as series are organized around writers, and artists are often subbed out during on-going stories. Within critical circles, analysis usually focuses on writing as well. Critics are themselves writers, so they are adept at talking about the literary elements. A comic’s plot, character motivations, dialogue, all these are well covered. I’ve seen many artists online bemoan the lack of discussion of their craft. Comics are at least fifty percent art, but when critics are themselves critiqued for having a blindspot when it comes to writing about the craft of image making, the response I see is a sincere plea for examples of how to even critique visuals. In Elsa’s videos I see a perfect lesson.

✧༺♥༻✧

Perhaps the most extreme form of this kind of analysis can be found in animation, particularly in anime. It’s colloquially called “sakuga,” and it has come to refer to the practice of accrediting individual shots to their artists. The original scope of the term refers to a cut of animation that is distinctly higher quality than the surrounding cuts, behaving kind of like a solo during a music performance. Those in the know recognize these soloists, and the artists gain some niche celebrity. Because this is the internet age, the scope of “sakuga” quickly exploded, and now any and every cut of animation can be sakuga, leading to a sizable fan community that researches as many individual artists as they can. This research even extends beyond key animators, and includes background artists, compositors, and more.

I am usually adverse to non-professionals making confident assertions about the behind the scenes of any piece of media, but sakuga strikes me as different. For one, the lack of NDAs means that the artists themselves participate in the discussions and can set things straight when cuts are miscredited. Secondly, the goal of these fans is not IP focused. Fan culture usually champions specific IP, but sakuga fans follow the individual creators to whatever shows they take them to, regardless of genre. Their goals are refreshingly non-commercial. They don’t root for a sports team, they chart every player in the league. They just want to learn about the talents and growth of individuals. They want to see how the visual grammar of animation evolves over time, and how it is shaped by human hands.

While sakuga discussions are non-commercial in the sports team sense, they are definitely not apolitical. The goal of sakuga analysis is to expand the spotlight beyond the typical director auteurs. A beloved show is made up from the contributions of so many people, and by highlighting each of them and placing them in a context that is both historical and personal, it gives power to voices that have otherwise been marginalized. But with new attention comes unavoidable realities. When you have a name and a face to the specific, tangible contributions that make up the stuff you love, it empowers their voices when they say “we’re barely scraping by.” Animation is undergoing a crisis. There are more shows being produced than there are resources to make them — human and monetary. The demand is high, and there is a bubble that appears on the cusp of bursting. Thanks to the fan communities that dig into the shows’ credits and honors people for their individual contributions, a complete outsider like me can understand what this ongoing crisis means for the real people suffering under it.

✧༺♥༻✧

Despite witnessing exploitation that would make a games executive blush, I am envious of this moment in comics and anime. There are horrifying injustices in those fields. Yet I look on to these critical analysis and research pieces for the crafts with longing, because games still seem so far from them. Yes, I am envious because I would love for my own work to someday be treated with such scrutiny and respect. (Anyone who says otherwise is lying!) But even more than that, I would love to be able to trace the individual contributions of people as they flitter through the games industry because there is so much to learn from! Were I to take any room in For Frog The Bell Tolls, Link’s Awakening, and Oracle of Ages I would find three dramatically different solutions to some of the same game design problems. Who did the layouts for those rooms? What led them to those conclusions? How did the outcomes of these games inform the next titles they worked on? As someone who works in the field, I can’t help but be transfixed by these questions.

Games are very secretive about how things come together behind the curtain. But I would hope that anyone who has worked on one knows that there is no job in it where the people are completely replaceable. Games are about finding solutions to made up problems, but no two people will land on the same solution. I get a little discouraged when I see fans clamor for sequels to games where the teams have totally dissolved, because the magic that made the originals is not in the IP, but in the chemistry of the team. We all want to know what makes one game click and another flop; or worse, never materialize. I believe we would have a better understanding if we could develop the vocabulary to express the quirks of the individual contributors. I have been inspired by many things this month to look closer at the credits of everything I play, and hopefully I will continue to learn things.

– Esteban

Links:

Shmuplations Interview: https://shmuplations.com/yasuhikofujii/

Elsa Charretier’s Channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Peu6lw0nido

Star Wars Within A Minute: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgS3pt0yMvs

Animetudes: https://animetudes.com/the-history-of-the-kanada-school/

Sakuga Blog: https://blog.sakugabooru.com/

If you have enjoyed reading this, consider signing up for the Saving Game newsletter! I will always post these on my website, but with the newsletter all future essays can go straight to your inbox.

Comments

One response to “Looking at the credits”

[…] Looking at the credits […]